Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is now officially recognized as a cancer-causing agent in humans, alongside hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV). This small, defective virus requires HBV to infect and multiply inside liver cells. It cannot infect someone independently, but when it coexists with HBV, it creates a far more dangerous health condition than HBV alone.

HDV infection is found worldwide but is more common in parts of Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe. People with both HBV and HDV infections face faster disease progression, severe liver damage, and a much higher risk of developing liver cancer.

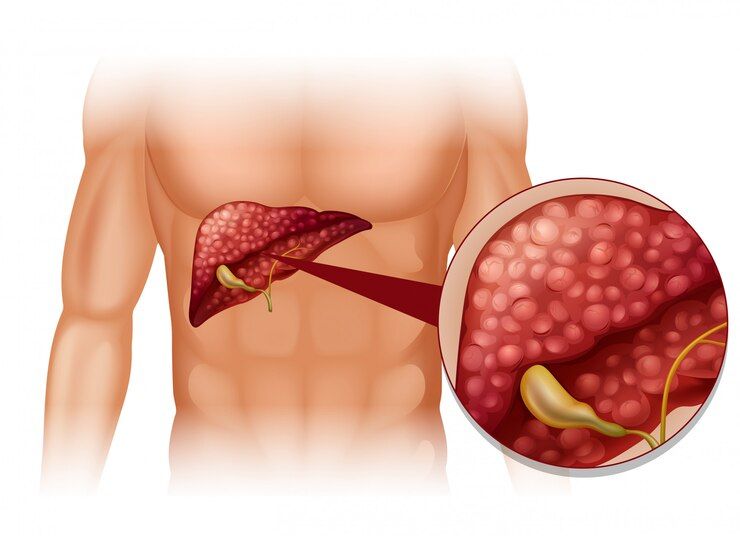

The virus causes liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC) by damaging DNA, disrupting normal cell repair, and triggering abnormal cell growth. HDV’s viral proteins activate pathways that promote cell survival, inflammation, and oxidative stress. These processes, along with epigenetic changes and severe fibrosis, create an environment where cancer can develop more rapidly. Cirrhosis present in up to 80% of people with chronic HDV infection dramatically increases the risk.

Symptoms of HDV infection are similar to other liver diseases, making diagnosis difficult. Common signs include fatigue, nausea, loss of appetite, upper right abdominal pain, dark urine, and jaundice. Because the disease can progress silently, early testing is vital especially for people already living with HBV who experience rapid liver deterioration.

HDV is transmitted through contact with infected blood or bodily fluids, similar to HBV. High-risk situations include sharing needles, unsafe medical procedures, unprotected sexual contact with an infected person, and, less commonly, mother-to-child transmission during birth.

Prevention is largely possible through hepatitis B vaccination, as HDV cannot exist without HBV. Completing the full HBV vaccine series provides protection against both viruses. Additional precautions include avoiding shared needles, practicing safe sex, and ensuring blood products are properly screened.

Treatment options for HDV remain limited. New drugs like bulevirtide aim to block HDV entry into liver cells, but prevention and HBV control remain the best strategies. Supporting liver health and closely monitoring at-risk patients are essential steps to reduce complications.

The recognition of HDV as a cancer-causing virus highlights the urgent need for greater public awareness, better diagnostic methods, and stronger health policies. With prevention and early detection, the severe outcomes of HDV including liver cancer can be significantly reduced.